One of the lithium sulfur coin batteries being developed in Penn State's Energy Nanostructure Laboratory (E-Nano).Image: Patrick Mansell

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — We have come a long way from leaky sulfur-acid automobile batteries, but modern lithium batteries still have some down sides. Now a team of Penn State engineers have a different type of lithium sulfur battery that could be more efficient, less expensive and safer.

"We demonstrated this method in a coin battery," said Donghai Wang, associate professor of mechanical engineering. "But, I think it could eventually become big enough for cellphones, drones and even bigger for electric vehicles."

Lithium sulfur batteries should be a promising candidate for the next generation of rechargeable batteries, but they are not without problems. For lithium, the efficiency in which charge transfers is low, and lithium batteries tend to grow dendrites — thin branching crystals — when charging that do not disappear when discharged.

The researchers examined a self-formed, flexible hybrid solid-electrolyte interphase layer that is deposited by both organosulfides and organopolysulfides with inorganic lithium salts. The researchers report in today's (Oct. 11) issue of Nature Communications that the organic sulfur compounds act as plasticizers in the interphase layer and improve the mechanical flexibility and toughness of the layer. The interphase layer allows the lithium to deposit without growing dendrites. The Coulombic efficiency is about 99 percent over 400 recharging discharging cycles.

Lithium sulfur batteries stored on a fast charger.Image: Patrick Mansel

"We need some kind of barrier on the lithium in a lithium metal battery, or it reacts with everything," said Wang.

Sulfur is a good choice because it is inexpensive and provides the battery with high-charge capacity, higher-energy density so a lithium sulfur battery has more energy. However, a lithium sulfur battery forms an inorganic coating in the battery that is brittle and cannot tolerate changes in volume. The inorganic sulfur interface cannot sustain high energy. In a lithium sulfur battery, the electrolyte dries up and the bulk lithium corrodes. The lithium dendrites that form can create short circuits and other safety hazards.

"Potentially we can double the energy density of conventional DC batteries using lithium sulfur batteries with this hybrid organosulfide/organopolysulfide interface," said Wang.

They also can create a safer, more reliable battery.

To create their battery the researchers used an ether-based electrolyte with sulfur-containing polymer additives. The battery uses a sulfur-infused carbon cathode and a lithium anode. The organic sulfur in the electrolyte self-forms the interphase layers.

The researchers report that they demonstrate a lithium-sulfur battery exhibiting a long cycling life — 1000 cycles — and good capacity retention.

Others working on the project include Guoxing Li, postdoctoral fellow; and Yue Gao, Qingquan Huang, and Shuru Chen, graduate students, Department of Mechanical and Nuclear Engineering; and Seong H. Kim, professor of chemical engineering and materials science and engineering, and Xin He, graduate student in chemical engineering.

The U.S. Department of Energy supported this work.

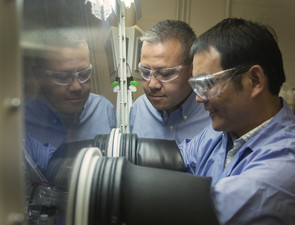

Donghai Wang, left, looks on as post doctoral candidate Guoxing Li assembles a lithium sulfur battery. Wang oversees the Energy Nanostructure Laboratory at Penn State's Materials Research Lab. His work focuses on nanomaterial development for clean energy technologies, such as batteries, solar cells, fuel cells, and environmental remediation.